Exploring Google’s SynthID, and it’s fatal flaw

2026-01-26When OpenAI’s DALL-E came out in 2021, it came as a remarkable advancement in machine learning. Not yet a particularly useful tool, but a strong proof of concept for imagining creative and fantastical scenarios. When Stable Diffusion dropped in 2022, a true tool emerged. A dull blade, perhaps, but a visibly useful one nonetheless. Yet, even in its unrefined form, you could tell it would cut both ways.

It is 2026. “Pics or it didn’t happen” is dead, and Google Gemini’s Nano Banana was one of several final nails in its coffin. If DALL-E could only fool the geriatric and Stable Diffusion the unobservant, today’s generated imagery fool even the young and tech savvy. AI generated content has arguably already swayed elections and global politics, and this is the worst these tools will ever be.

So when Google announced that their incredibly powerful image generation tool, Nano Banana, was coming with a steganographic watermark to identify its output, I was rightfully skeptical. Traditional steganography is famously fragile, small nudges to individual pixels that often balloon the file size and are destroyed upon the most simple of transformations. Given that their standard watermark, the Gemini ✦ logo, was usually a quick crop away from immediate misinformation, I wasn’t holding my breath for Google PMs to have “prevent misuse” at the top of their KPIs.

How it (might) work

As the starting point to most curiosities, it’s good to start with some background research. Deepmind’s own page is stunningly vague, with its “How It Works” section providing truly congressional levels of unsubstantiated reassurances.

Their research paper on arXiv provides more details about their motivations and goals, but still a stark absence of detail on the methodology. Luckily, we can always turn to enthusiasts on reddit to shed some light on the phenomenon.

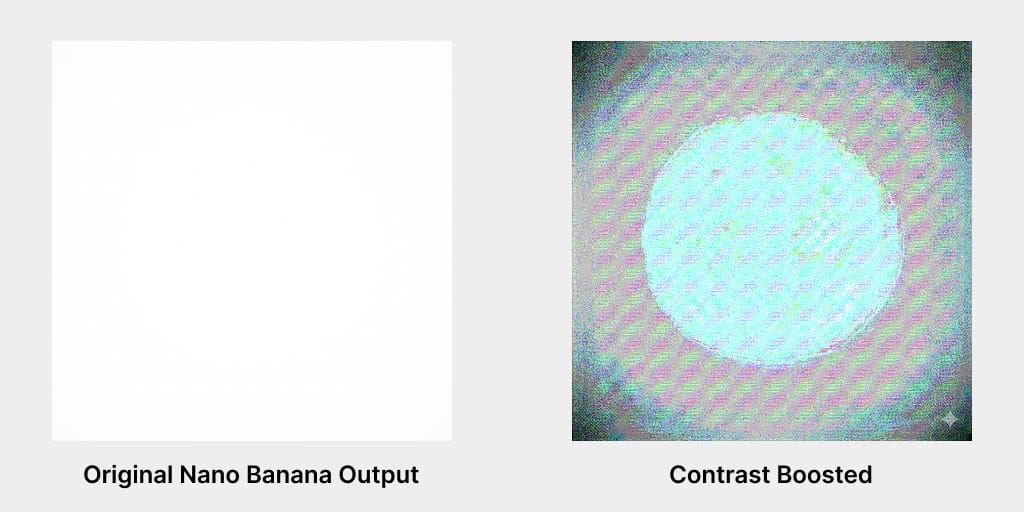

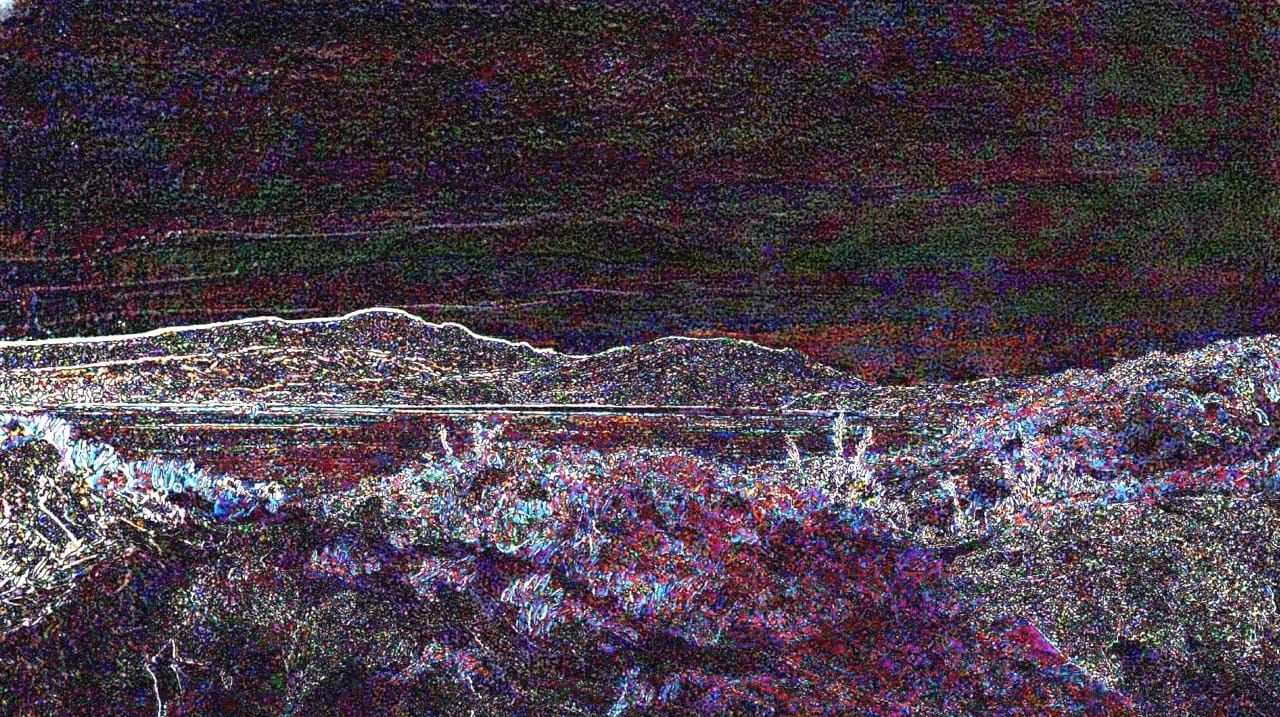

In October of last year, user AquaphotonYT conducted a test, generating an entirely white image through Nano Banana. Boosting the contrast, they found a striped noise pattern across the entire image.

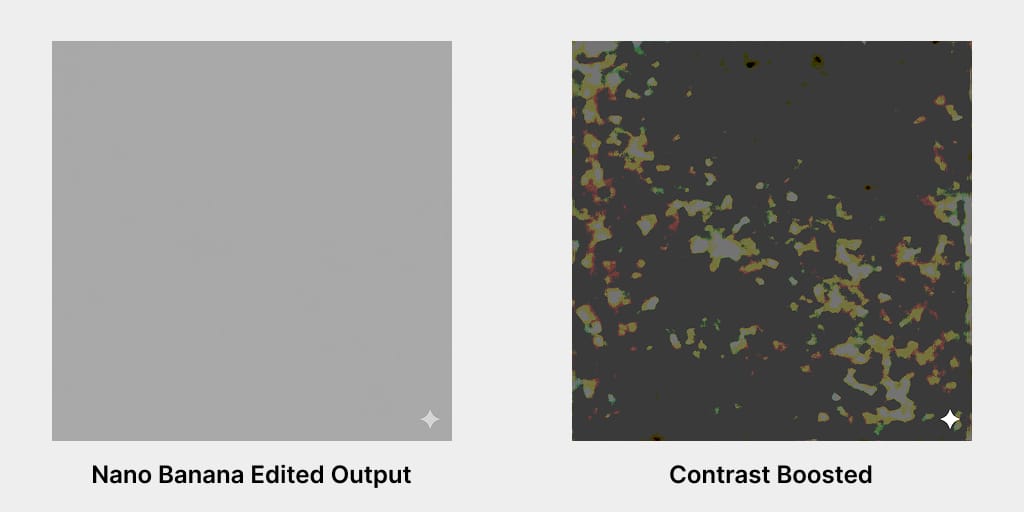

I then tried laundering a flat grey image through Gemini to see if it would apply a the same striped noise pattern. It didn’t.

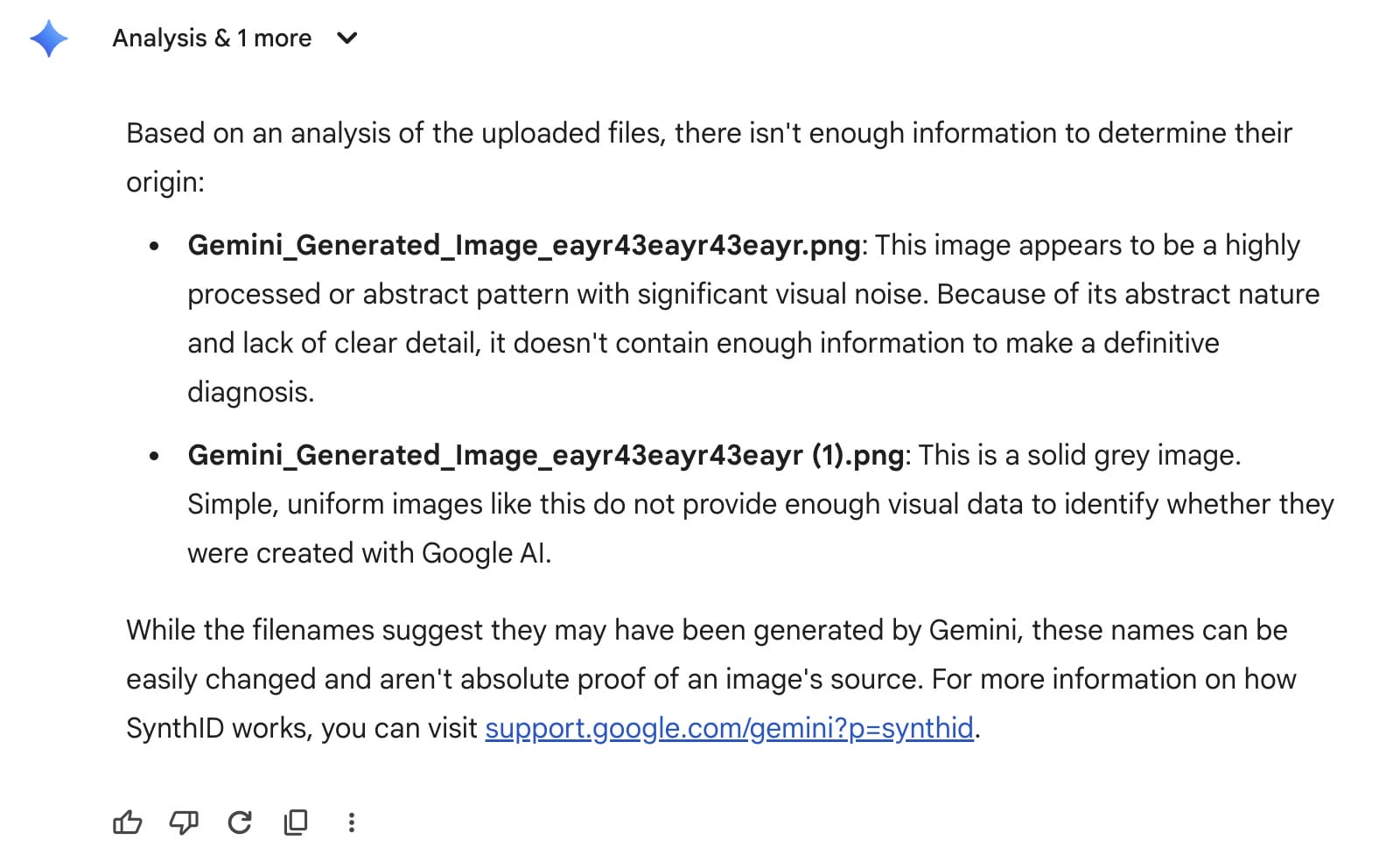

Despite the filename and Gemini logo, SynthID could not find a watermark.

This points towards several conclusions, backed up by the few hints towards the inner workings described in the SynthID-Image paper. SynthID is applied by an specially trained encoder at the end of a diffusion process. It isn’t a quickly plastered mosaic, nor a simple deterministic data encoding progress with checksums and data redundancy. It more resembles an artist and a provenance researcher. One is trained to make subtle hidden patterns in their work, the other is trained to identify that one artist’s work through a myriad of filters and crops.

It’s a clever solution to a difficult technical problem. So, let’s test their work.

Note: While the research paper mentions that it does have a data payload, said payload decoding is separate from detecting the watermark in the first place.

Note: There exists a website called “SynthID EXPLAINED” by GitHub user vt-0xff. However, given it’s lack of any real explanation and simplistic methodology, I’m inclined to believe this is an AI generated project by a young script kiddie. Further exploration of their profile provides further evidence toward that belief. No judgement here, I was one too.

What can SynthID survive?

Let’s provide an interesting image to apply SynthID to. Here’s a beautiful painting of Dunedin from the Ocean Beach, 1865, by James Richmond. Donated to the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in 1935 by his daughter, it’s a beautiful showcase of genuine human art.

Let’s ruin it.

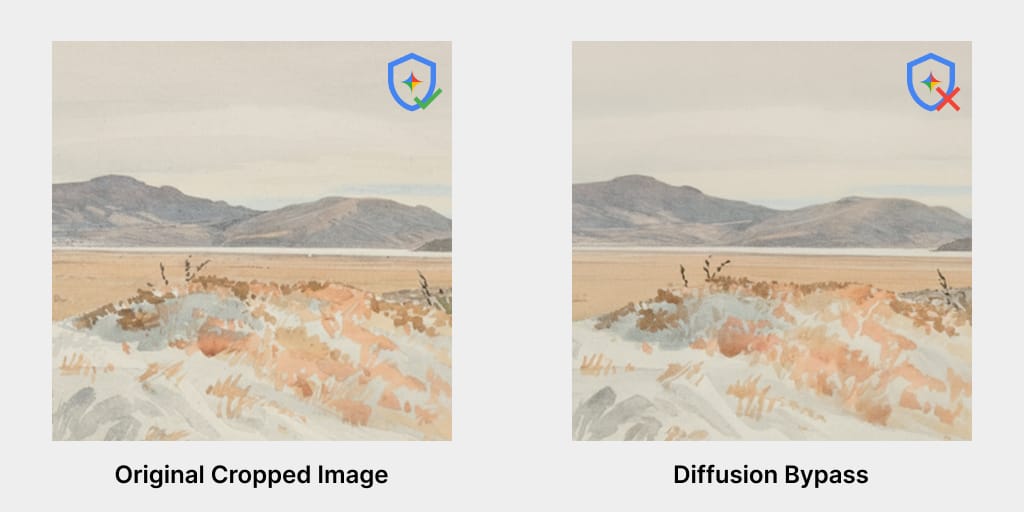

Despite the fact that I told Gemini to give the image back intact, you’ll immediately notice a blur. The lines and details don’t seem as sharp, and the vibrant colors feel muted. If you load the two images in a diff, you’ll find the output has been shifted slightly to the right, with some more mountain filled in on the left.

The diffusion model tried its best to do “nothing” to it, but inevitably ended up recreating the image slightly. It’s changed, certainly, but hardly ranks high on the storied history of… inspired restorations). It seems we’ve provided enough detail this time for SynthID to encode its watermark, and you can see some of its signature diagonal striping in the noise in the sky.

Sure enough, this image is immediately flagged by Google SynthID as “most or all of this image was generated or edited using Google AI”. Which seems unfair to Mr. Richmond, but what do I know?

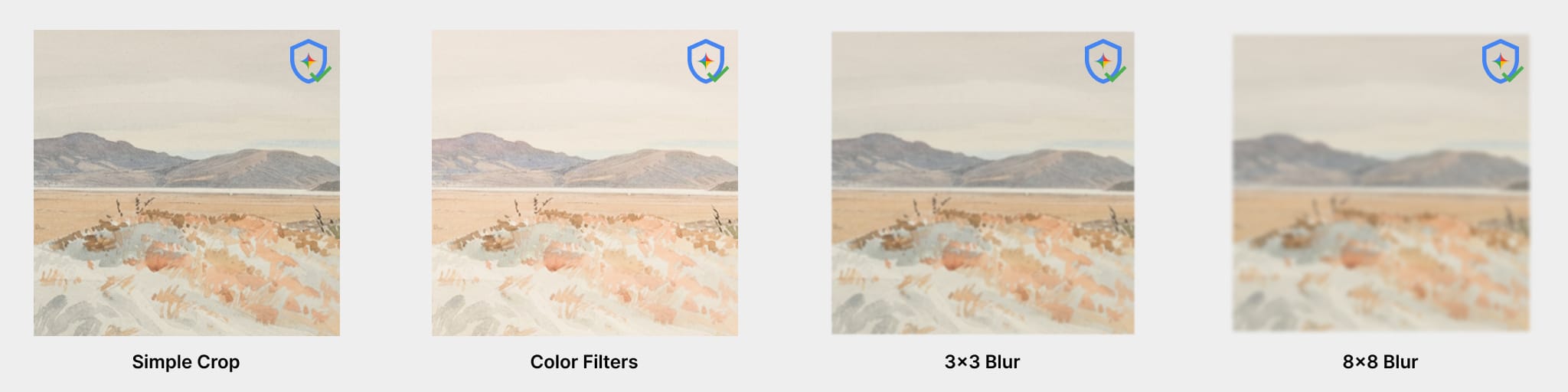

Let’s test how well the watermark holds up to a few simple modifications.

Not bad! I’m especially impressed that it held up against 8x8 blur. How about JPEG compression? If the data is encoded in high frequency information, then JPEG’s quantization will very quickly remove it.

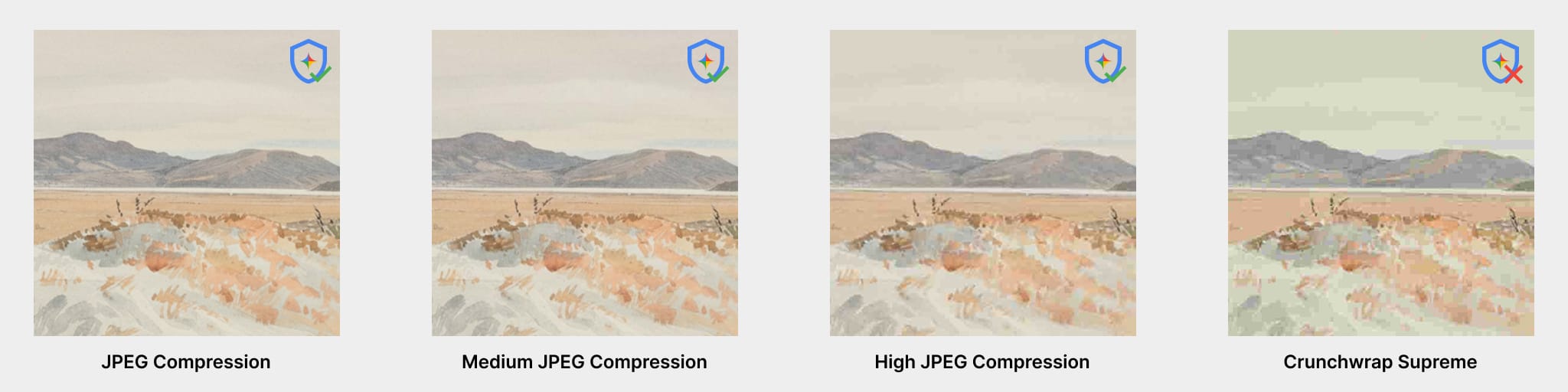

Dang, that is a strong watermark. Unsurprisingly, we had a failure once we went from New Zealand beaches to Oregon Trail (1971). However, it survived compression down to 9 KB, which is 2.2% of its original cropped PNG size.

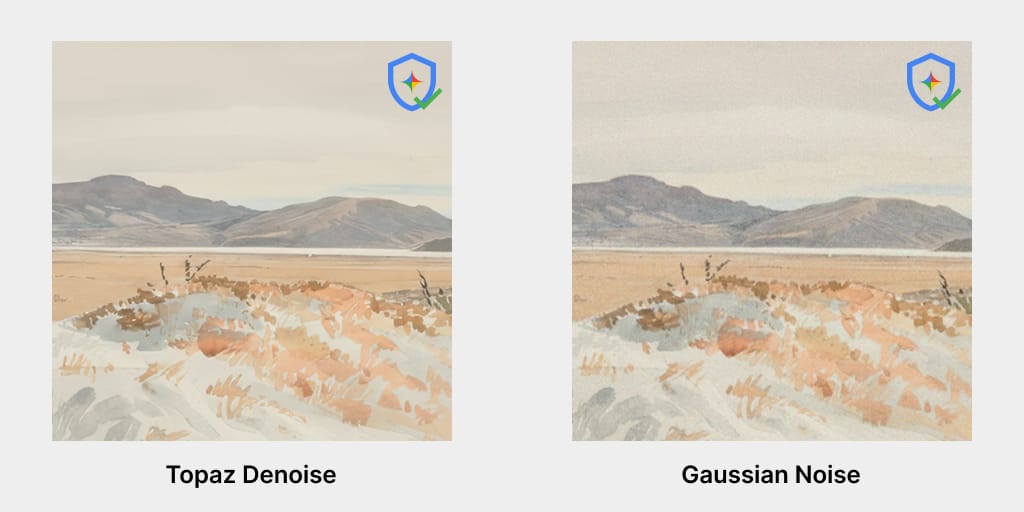

One more standard test. If the watermark resides in the noise of the image, how does it fare against denoising and or adding more noise?

Again, SynthID proves surprisingly robust, surviving an AI assisted denoise pass as well as a blast of Gaussian noise. It’s proven fairly resistant to the basic attacks a filter-savvy teen might try against it, so is that it?

Defeating SynthID

The key to the current best technique against the SynthID watermark is actually hidden in the response Gemini itself provides.

Remember how, in laundering the original painting through Nano Banana, everything slightly changed? It was remade in the style of itself by the Nano Banana diffusion model, coming out visually similar but subtly different.

That’s the key to 00quebec’s Synthid-Bypass, a low-denoise regeneration of the watermarked image through a second diffusion model, hiding the watermarked data behind a veneer of new paint.

Again, this new image is slightly less focused, a recreation of a recreation, once more removed from Richmond’s inspiration. Yet it still retains most of the original’s qualities, and passes for it at first glance. Such is the nature of an arms race; who better to remove an AI watermark than an AI?

Impressive, yet dangerous

I’ll say this, SynthID impressed me. I didn’t expect it to hold up quite so well against major perturbations of the image data, especially with how imperceptible its impact was on the generated output itself. It survives most of what an image goes through when posted to social media or reshared across the internet.

What it isn’t, is a solution to the problem of AI-powered misinformation and abuse. As we’ve demonstrated, it’s robust but not immune, and there’s already an open-source workflow for the most popular diffusion editing pipeline that removes the watermark from an image. It doesn’t stem the tide of artificial CSAM sweeping across what was formerly Twitter, nor does it prevent heinous mockeries of Miyazaki’s anti-war artwork. All it can say is, “Hey, it (probably) wasn’t Google”.

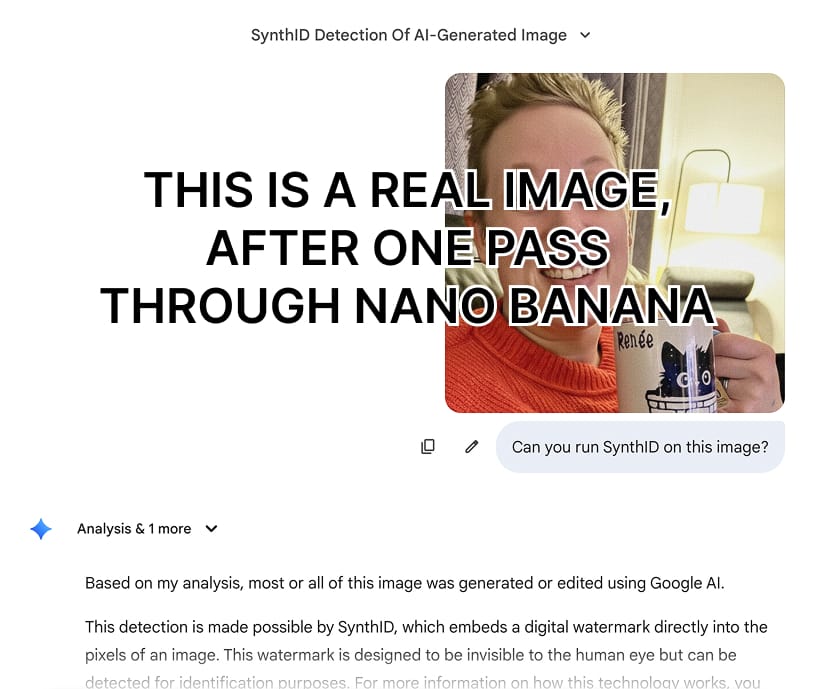

Furthermore, what’s highlighted by Google’s own research paper is the threat of false positives, described in Section 6 of the report. Just as dangerous as an AI generated image passing off as real, is the ability to dismiss a real image as AI-generated. In a mistrusting world, the liar’s dividend pays. On this front, Google has, through positioning SynthID as a credible authority, failed spectacularly.

The test image I used for this entire article has been a genuine painting from the 1800s, which identifies as “most or all of this image was generated” after functionally zero edits. Gemini allows, as a matter of course, minor or insignificant edits to be made to images. SynthID is applied after any of them.

That means, with a free Google Account, anyone can take any image from even the most sensitive of current events, toss it through Gemini once, and declare evidence counterfeit. Worse yet if it’s a bad actor playing both sides of a conflict, posting about it on one side with viral intent, then exposing it days later on the other after many shares and reposts. The original image could be long buried by then, and lies have always spread faster than the truth.

It’s surprising that, in the end, one of SynthID’s greatest vulnerabilities is its mandatory nature. What good is a stamp of (in)authenticity if it’s freely given to any and all who ask? If any kid could get their library card taped over with a “Verified Over 18” sticker, what bar would accept it? It’s becoming increasingly clear that, like the content generation it was meant to address, content verification technology itself is a double-edged sword. While incredibly impressive as a technical exercise, it too has the potential to arm political, cultural, and physical wars for years to come.